SAINTS - AN INTERVIEW WITH DR AMY JEFFS

The author of a beautiful and brilliant new book on medieval saints talks about history, art, relics and assassinations

A few summers ago - could it even have been before the pandemic? - Dr Amy Jeffs came round to my house for lunch.

We sat in the garden on a warm day and ate Greek salad with watermelon, then repaired to the kitchen where, on the island, Amy laid out a selection of astonishingly beautiful linocuts she had made, illustrating scenes from the mythical history of Britain, shuffling them around while she told me the stories that lay behind each one.

That was a great privilege at the time, and feels even more so now Amy is a bestselling author, whose debut book Storyland: A New Mythology of Britain was a Waterstones Book of the Year.

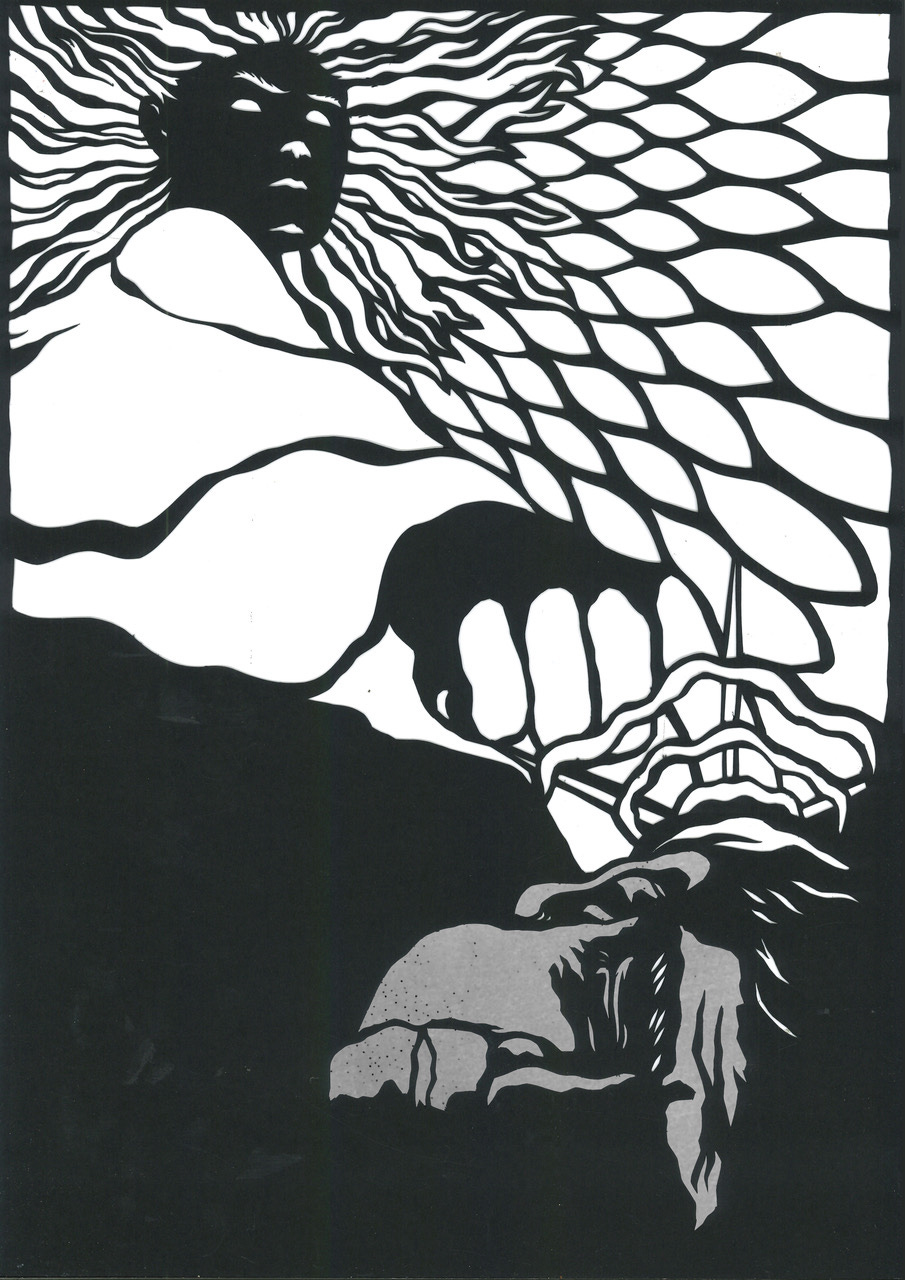

Yay upon yay, therefore, that Amy’s third book, Saints: A New Legendary of Heroes, Humans and Magic will be published in a few days. It is a beautiful blend of original artwork, retellings of saints’ legends and erudite historical discussions of their origins and development. I heartily urge you to pre-order a copy. In the meantime, here is a conversation between Amy and me about… saintly things.

DJ: Most people today could probably name at least a couple of saints - even if it’s just Saint George (the dragon-slayer) and Saint Nick (a.k.a. the devil, or Father Christmas). In that, we’re very different from medieval Christians. Can you give us an impression of just how different? What role did saints play in day-to-day life during the Middle Ages?

AJ: Sometimes mockery sheds light on everyday things that don’t otherwise get written down. One of the stories I retell in Saints comes from an obscene Old French poem called St Martin’s Four Wishes. The main character, a farmer, swears by St Martin so much in his daily activities, that the saint appears to him, genie-like, and gives him four wishes.

The farmer runs home and tells his wife who persuades him to let her make the first wish. Her husband agrees and she asks for her him to be covered head to toe in penises (his one cock never having been enough). Hilarity ensues for three more wishes, but the story rests, crucially, on the assumption that readers will know people who swear to saints with every other breath.

While the farmer is a stock character, the gullible rustic, he also reflects the way in which devotion to saints suffused the language and religious beliefs of the Christian population. Saints were protectors, differentiated by their legends and their special areas of interest. Whether in the form of pilgrim souvenirs or verbal oaths, people carried their patrons with them everywhere.

DJ: Your new book, Saints, is beautifully illustrated with your own artwork - in paper cut-out, rather than the linocuts of your earlier books. Could you tell me about your creative process? What comes first - the inspiration for the illustrations, or the stories?

For me, it has always begun with an illustration in a medium that captures how I want the book to feel. Until I see that image, I’m all at sea about what the tone of the writing should be or the mood of the stories. I wrote a whole draft of Saints before I realised I didn’t want to use linocut or wood-engraving after all, at least not for this book. Then I did my first two paper cutouts (St Christopher wading through the flood and the Archangel Michael using his finger to sear a hole in the head of the Bishop of Avranches) and I saw what I wanted for the project. After that, I wrote the book again, a new and much happier wind in my sails.

DJ: Your historical background is one of working hands-on with medieval illuminated manuscripts. Do you think that the integration of illustration and text is essential to getting oneself into the mindset of medieval reading? I suppose I’m saying: are you a latter-day Matthew Paris?

AJ: Some manuscripts are patchworks of different scribal hands, different artists, while some — rarities — are like they’ve been sneezed out of one medieval brain. I spent three years of my PhD in blissful contemplation of a 14th-century manuscript written and illustrated in the same tone of brown ink, with the same slightly wobbly style (BL, Egerton MS 3028). I love that out-growing of image from word and back again. I love the sense of unity. And, yes, you get that with Matthew Paris’s autograph works like the Chronica Maiora. They are totally one-off. I wanted to evoke that unique visual and textual unity with Saints. And, yes again, I often wish I was a 13th-century Hertfordshire polymath chronicler monk, if a touch more woke.

DJ: You make a distinction in your book between saints whose stories are derived from Scripture or the martyrology of the early Church, and those who were canonised after about 1200. How did saint-making change at that point?

AJ: An objective for this book was to show the surprising (to me, at least) artificiality of saints’ legends, especially early ones. Even when the subjects can be traced to historical figures, the legends draw on tropes and patterns found in folklore and myth; they share a common storytelling heritage.

With some notable exceptions (such as the most excellent Uncumber), saints whose cults postdate 1200 are more straightforwardly historical. Miracles still proliferate, of course (take the Wiltshire woman raised from the dead by Henry VI, who kept her shroud on in witness to the wonder; I imagine her hopping through her hometown of Mere), but there’s a greater formality to the legends themselves. Things change after 1200, primarily due to the Papacy’s interest in keeping closer tabs on the process of canonisation.

DJ: Is there any particular saint to whom you are especially drawn? Or a story that you find irresistibly compelling/weird?

AJ: Saints are intrinsically ‘weird’, in the medieval sense of ‘one able to control fate’. In Saints I explore how people’s veneration of saints led to the use of incantations and talismans that might well count as ‘religious magic’. These practices, which were thought to guarantee a result if performed correctly, troubled theologians for the whole history of the medieval cult of saints.

At the shrine of Thomas Becket, pilgrims could buy small lead-tin vessels called ‘ampullae’, which contained water tinged with Becket’s blood. In one miracle report (a genre of medieval literature I earnestly recommend), a Canterbury woman called Agnes, afflicted with a weeping facial tumour, drinks the water from an ampulla. At once, a horned, sharp-tailed little devil creature, red as a hot coal, writhes out of her mouth and into the bowl she has been using to collect the pus from her face. The creature disappears, but not before her friends have witnessed the miracle, and she goes on to make a full recovery.

Some Becket ampullae bear the inscription ‘Thomas is the best doctor to the worthy sick’. It implies that the efficacy of the talisman lies not with the will of the divine, but in the purity of the recipient. It’s a subtle distinction, but an important one when it comes to understanding why the cult of saints was so central to the violent debates of the Protestant Reformation.

Magic was real, but the wonders it yielded were not of God. The Devil could work wonders too. I suppose, therefore, my answer is that I am most drawn to the growing dissent in late medieval north-western Europe about where the devil is hiding: in a malignant tumour or the trinkets sold at a holy shrine?

DJ: Is there any equivalent of the cult of sainthood in the modern world? Either with regard to mythologising individuals or the collection of ‘relics’? I noticed this week that one of the candidates standing for election as the next President of the United States has cut up the suit they wore to a particular political debate, and is selling it off in tiny strips to political donors, on the understanding that this is a way to ‘own a piece of history’. This is not the place for political grandstanding (although feel free to do so if you wish) but I immediately thought of the medieval relic-trading tradition…

AJ: This is a fascinating and brilliant question. Relics and contact relics (i.e. human remains or items touched by the saint), are an enormous part of the medieval cult of saints, especially for the first few hundred years of its existence. But relics are not in the Bible; the idea is not Scriptural. Rather, I think relics reflect an existing and perhaps universal human love of having things on which to focus our devotion, on which to hang stories, with which to perform wonders.

In the early Middle Ages, relics were an invaluable tool for missionaries campaigning to convert the populations of northwestern Europe. They became focal points in the new churches. In Fulda, Germany, pilgrims could visit the Ragyndrudis Codex, slashed, as if with a metal blade, which, it was said, the missionary St Boniface had held over his head as pagans hacked him down. We only need to search auctions for the personal items of assassinated, or almost assassinated, celebrities to know this macabre impulse endures. But it is rooted, perhaps in a more quotidian relationship with souvenirs.

My fascination with medieval saints’ legends began during my time working with the medieval pilgrim souvenir collection at the British Museum. Many were and still are found in the muddy beaches of the Thames in central London. In these cheaply made objects, saints’ legends and the personal memories of medieval pilgrims converge. We can tell the legends again and we can imagine the memories. And yes, while much in my new book seeks to challenge our compulsion to make the past superficially relatable, dig far enough and we find ourselves again.

Saints: A New Legendary of Heroes, Humans and Magic by Amy Jeffs (Riverrun, £30), is published in the UK on September 12th.

Another comment - I really loved the Medici chapel in Florence and their epic collection of relics.

Ever since I was a kid I loved reading about the lives of saints. This looks fascinating- I always enjoy your book recommendations