WAS THIS THE BADDEST MAN ON THE MEDIEVAL PLANET?

A guest post from bestselling author Helen Carr

From time to time on History, Etc, I like to hand over the keys/reins/work to someone else. Today is the turn of Helen Carr, whose forthcoming book Sceptred Isle takes a deep dive into the occasionally rather inglorious fourteenth century.

Here Helen considers the career of Hugh Despenser the Younger - who managed, even in a rough age, to make a name for himself as staggeringly nasty piece of work.

If you want to pre-order Helen’s new book, you can find more details here. She also writes a Substack, called In History. Her other books include a bestselling biography of John of Gaunt.

Over to her.

The most notorious villains in medieval history are often caricatures, written into popular legend to serve the quality of a story — the Sheriff of Nottingham (I’ll cut your heart out ...with a spoon) comes to mind.

Some were real and really bad. King John who famously murdered his own nephew, Arthur of Brittany, before throwing his body into the River Seine. Or Richard III, who (come on) had his two young nephews murdered in his care. These are household names, known mostly for their Machiavellian methods of climbing the greasy pole to power.

I knew when writing Sceptred Isle: A New History of the Fourteenth Century, that I would encounter an appalling amount of bloodshed, cruelty and a fair share of villainy. This was a century of civil war and the start of the Hundred Years War, bookended by two regicides — there was a lot of political and literal back stabbing.

What I did not expect was the political violence that was levelled at women and in the first phase of the fourteenth century there was one man swinging the sword — Hugh Despenser the Younger.

The son of a prominent nobleman (also named Hugh Despenser) Hugh Despenser the Younger was a loyal crony to Edward II from his accession to the throne in 1307. Despenser the Younger was married to Edward’s niece Eleanor de Clare and was a similar age to the new king, meaning he was one of the principal members of the king’s courtly coterie.

Edward II’s reign was dominated by his problem with favourites. The close relationship Edward fostered with the haughty and debonair Piers Gaveston fractured the political landscape of the early 14th century before Edward even had the crown on his head. He made Gaveston too important for no real reason other than because he could and because he adored his friend, or supposed lover.

All of this alienated the nobility, who had a strong sense of God-given hierarchy and a staunch belief in their own importance. When the comparatively ‘low born’ Gaveston — a former squire — was given an earldom and acted as custos regni (effectively regent) a contemporary account describes there being ‘two kings’ in the realm. After a litany of threats were hurled at Edward II — deposition and the exile of Gaveston — his favourite was eventually captured and beheaded by the order of Thomas of Lancaster, Edward’s cousin and resident fun sponge.

In hindsight — and a lot of history is hindsight — Gaveston’s enemies would have done well to let him quietly get on being annoying and rude, for in comparison to the man who would replace him Piers Gaveston was a pussycat.

Hugh Despenser the Younger was cunning, manipulative, aggressive and violent. One account describes him as a ‘monster’; another, ‘full of evil and wrongdoing…greedy and covetous’. In one case, before shocked members of parliament at Lincoln Cathedral, Despenser attacked a knight named Sir John Ros, ‘striking him with his fist until he drew blood’. Despenser wanted it all — power, title and wealth. Nothing was off limits to him with the king on his side and he had his sights set on the glittering prospect of the earldom of Gloucester.

In 1314 the earl of Gloucester, Gilbert de Clare, was killed at the Battle of Bannockburn, leaving a power vacuum in the Welsh Marches — land the earldom encompassed. He left as his only heirs his three sisters, Eleanor, Elizabeth and Margaret and the earldom was duly split between these three sisters and their husbands. Despenser, being married to Eleanor, was the recipient of a portion of the inheritance. The De Clares were the most powerful family in the region. The Mortimers were another influential bunch — a military family, with Roger Mortimer of Wigmore having served Edward II in Ireland.

These Welsh lords were effectively fourteenth century oligarchs. They danced to their own tune and managed land independent to the crown. Having more authority over these lords was a tempting prospect to Edward II. For Hugh Despenser more land and wealth was an equally tempting prospect, one that could become reality with the intervention of the king.

Through a series of threats and by tying Elizabeth and Margaret de Clare (and their husbands) into an administrative spider’s web, Hugh Despenser the Younger managed to acquire the entire Gloucester inheritance, all sanctioned by the king. Other lords with land across the Welsh March were baffled and threatened by this seemingly unstoppable man. He had become too powerful with the king as his ally. Roger Mortimer, Roger Damory (the now poor husband of Elizabeth de Clare) and Hugh Audley (the now poor husband of Margaret de Clare) amongst others, formed a coalition with Thomas of Lancaster. After years of political tension England plummeted into civil war, reaching its nadir with the Battle of Boroughbridge and the capture (and subsequent execution) of Thomas of Lancaster.

Edward II and Despenser had won. Of the Marcher lords, Roger Mortimer was imprisoned in the Tower of London and Roger Damory, Elizabeth de Clare’s husband, was mortally wounded. Elizabeth was arrested along with her children and her experience at the hands of Hugh Despenser was later inked into a secret document — A Protest Against the Despensers — which only surfaced when she was safe to reveal it. Her Protest is a haunting one, peppered with the word ‘gree’ meaning ‘will’ or the stripping of it. She wrote that ‘mon corps et de mes terres’, (my body and my lands) were in the clutches of the king and his dangerous favourite.

Elizabeth was one of many women who were appallingly treated by the king’s best friend. Alice de Lacy, the wife of the now dead Thomas of Lancaster was forced to forfeit her estates. (If she failed to comply, Despenser threatened to have her burned alive.) Margaret de Clare, Elizabeth’s sister, was stripped of her property and sent to live with the nuns in Sempringham priory. Lady Badlesmere, the wife of another lord who rebelled against Edward II and Despenser, was imprisoned along with her children in miserable conditions — her husband was butchered.

Under the orders of Hugh Despenser, Lady Baret, another widow of Boroughbridge, was ‘beaten… and shamefully had her arms and legs broken’. The record is littered with accounts of women — the wives and mothers of lords who had rebelled and been defeated at Boroughbridge — being forced from their properties and imprisoned.

Despenser did not stop with the nobility. He soon went after Queen Isabella’s prominent lands in Cornwall, hoping to add to his portfolio of wealth stolen from vulnerable women. At the apex of Despenser’s power, Isabella escaped England, travelling to France and her brother’s court in Paris on a diplomatic mission.

Isabella refused to return, publicly announcing, ‘I feel that marriage is a joining together of man and woman, maintaining the undivided habit of life, and that someone has come between my husband and myself trying to break this bond; I protest that I will not return until this intruder is removed, but discarding my marriage garment, shall assume the robes of widowhood and mourning until I am avenged of this Pharisee’. Revenge was what Isabella wanted and in 1326 when she crossed the Channel with an army at her heels, she had the single intention to drag Hugh Despenser the Younger to the scaffold.

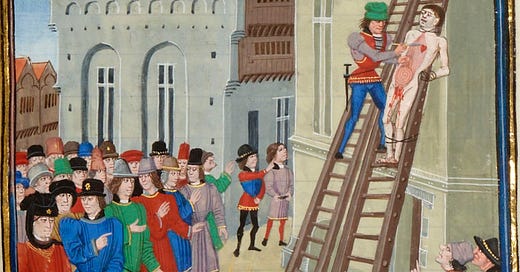

In a bloody coup, Isabella, nicknamed the ‘She Wolf of France’, had Despenser arrested and brought to trial as a, ‘traitor, tyrant and renegade’. The hated Hugh faced a miserable fate. On a gallows at Hereford, Hugh Despenser, wearing a tunic emblazoned with Psalm 52: ‘why do you glory in malice, you who are mighty in iniquity’, he was stripped naked and hauled into the air by the neck.

Suspended before the crowd, he was disembowled, his entrails yanked from his body and cast into a furnace below. Despenser’s penis was severed from his body and also flung into the flames — intended to symbolise the destruction of his line. Finally, he was beheaded and quartered. This man was so awful, encroached on royal power and cruelly capitalised on the vulnerable, his death had to be the bloodiest and most horrific spectacle this queen could conjure.

The general rule in medieval history was that, if you found yourself at the top of the Wheel of Fortune by crushing those below, the Wheel would spin and you would find yourself beneath its unforgiving spokes. Hugh Despenser the Younger’s cruelty to women in particular is staggering. There is a strong sense of judicial irony that his appalling death was at the hands of the only woman he was unable to overpower.

I knew he was awful but wow! Fabulous read and I can't wait for the book. I am just starting the Eagle and the Hart now! As for the wheel of fortune, as someone living in America right now I hope that the wheel will turn and crush those dismantling our democracy with cruelty and ineptitute. Shall we call him Musk Despenser?

I can’t wait to get the book! Thank you as ever Dan for recommending new books on Plantagenets! We junkies need our fix!