THE STORM THAT RUINED A MEDIEVAL WORLD RECORD

Britain has a long history of being battered by storms - and in the Tudor era, a violent storm brought down one of our greatest buildings

Note to readers: This is a free post from History, Etc. If you’d like to receive more content, including subscriber-only articles, Q&As, podcast episodes, giveaways and more, please sign up here. Paid subscriptions keep this newsletter going.

If you’re already a subscriber, thank you. Enjoy the read.

It’s blowing a gale in Britain at the moment. I arrived home at dawn this morning to find the main street in the town where I live closed to traffic: debris from a building site was scattered all over the road. In my garden, lights have been smashed and my outdoor furniture has been dancing free on the lawn. And the fence has blown over, its wooden pillars snapped like lollypop sticks.

This is, of course, far from the worst to have happened here in the last few days. High winds have killed people and destroyed property. The electricity supply has been disrupted and parts of the transport network shut down. Brits are known for their obsessive complaining about our generally mild, if changeable weather. For once we have something to moan about.

Yet as I stood and looked at my broken fence and fretted about my patio set this morning, I reflected that destructive gales have been a part of our history for centuries. People of my age still talk about the hurricane of 1987, which wreaked terrible damage across southern England, blowing down millions of trees and shutting down much of the National Grid.

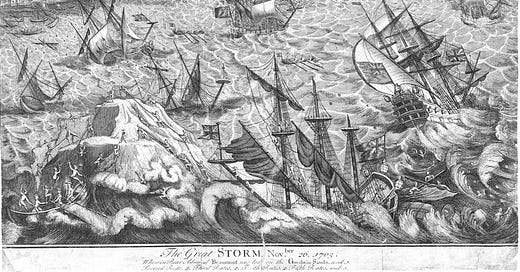

Even worse was the Great Storm of 1703, which killed thousands of people, sank scores of ships, blew over homes and windmills and took the roof off Westminster Abbey. In Daniel Defoe’s book The Storm (1704), often considered the first work of modern journalism, Defoe wrote of winds so strong that many people thought they were accompanied by an earthquake.

Defoe and many of his contemporaries thought the storm was the work of an angry God.

Horror and Confusion seiz’d upon all, whether on Shore or at Sea: No Pen can describe it, no Tongue can express it, no Thought conceive it, unless some of those who were in the Extremity of it; and who, being touch’d with a due sense of the sparing Mercy of their Maker, retain the deep Impressions of his Goodness upon their Minds, tho’ the Danger be past: and of those I doubt the Number is but few.

(You can read The Storm online here.)

The great storm that always sticks in my mind, however, is the one of 1548. In January of that year, a gale knocked the great lead-clad spire off the central tower of Lincoln Cathedral. The spire crashed into the cathedral roof, doing further damage to the fabric of the building. The roof was repaired, but the spire was not. So, impressive as Lincoln cathedral is today (and it’s one of my favourite buildings), during the earlier sixteenth century it would have been even grander.

Indeed, from 1311 to 1548 Lincoln’s central spire had made it the highest building anywhere in the world, taller than the Great Pyramid of Giza. Only in the 1880s, when the Washington Monument was dedicated and the Eiffel Tower built, did any buildings rise so high again. So if we’re feeling dramatic, we might say that this Tudor storm did not just decapitate a building. It struck a blow against human achievement which took centuries to overcome.

And I think we are feeling dramatic, when it comes to the weather. Although, as Defoe noted in 1704, Britain has always been known for its susceptibility to strong winds, we are today particularly sensitive to their occurrence.

The world’s climate is changing, a fact and a trend that is reported by the media in terms that are seldom far from apocalyptic. As a result, any example of severe and destructive weather feels like another confirmation of our impending climate-led doom.

This is in part our version of the psychological reaction as sixteenth-century and eighteenth-century Britons to bad weather. They blamed God. We blame ourselves. You can make of that what you will: it’s probably a subject best saved for another time.

All that matters for now is that the wind keeps blowing, things keep falling over, and I need to call a man about coming round to put my fence back up.

Look after yourselves.

Thank you for pointing out all the historical parallels, Dan. It puts things in perspective.

My husband was willing our fence to break in the winds (wants a new better fixed one). He clearly is a non-believer in both professed Deities in this thread now as it didn't fall.. Although some near neighbour must have thought good drying weather as we now have their bed sheet stuck up our tree