OUTLAWS SERIES #2: FULK FITZWARIN

The real-life outlaw who came to blows with King John was not Robin Hood - though his story probably inspired that more famous medieval renegade

When King John of England (r. 1199-1216) was a child he liked to play chess. That, at any rate, is the contention of the tale of Fouke le Fitz Waryn, an Old French prose romance blending fact and fiction, which was composed in the later thirteenth century. John, we are told, liked chess. Unfortunately, he also liked quarrelling. And one day, those two interests collided.

‘It so happened that one day John and Fouke [hereafter anglicised to Fulk] were sitting all alone in a room playing chess,’ goes the story.

John picked up the board and struck Fulk a great blow with it. Feeling the pain, Fulk raised his foot and delivered John a swift kick to the chest. John’s head struck the wall so hard that he became dizzy and fainted. Fulk’s immediate reaction was fright, but he was glad there was no one else in the room with them. He rubbed John’s ears, and he regained consciousness. John immediately went to the king, his father [Henry II], and lodged a complaint.

We can well understand Fulk’s moment of panic. According to the tale, Fulk was a childhood companion of all Henry II and Eleanor of Aquitaine’s sons - Henry the Young King, Richard the Lionheart, Geoffrey of Brittany and John. But there was a significant difference between being a child at court, and being a son of the king. Fortunately for Fulk, old Henry was a wise ruler first and a doting father second. He sided against John.

“Be quiet, you good-for-nothing,” said the King. “You are always squabbling. If Fulk did all you said, you most likely deserved all you got.” He called the boy’s master and had the prince soundly whipped for his complaint. John was very angry with Fulk, and from that day forward never had any true affection for him.

[Translation by Thomas E. Kelly, printed in S. Knight and T. Ohlgren, Robin Hood and Other Outlaw Tales]

We should stress again that this story is from a romantic outlaw tale. Yet to those of us who know our Plantagenet history, it has the ring of deep truth. There is so much that is absolutely plausible: John’s unprovoked and sudden recourse to physical violence; his refusal to stick to the rules of a game; his mistreatment of a close companion; his weaselly tale-telling; his entitlement; his easy intimidation when confronted; his total hopelessness at fighting, even when he had apparently stacked the odds in his own favour; his surprise at predictable political outcomes; his grudge-bearing; his bad luck.

Even if no chess game, no fight and no whipping ever occurred (and in all likelihood they did not), the value of Fouke le Fitz Waryn as a historical source is not totally negated. All we need remember is that it is not reportage, but a parable.

The outlaw tale in which we usually meet King John today is Robin Hood, where John is presented as the epitome of corrupt kingship, in contrast to his just and valiant brother Richard. Yet as we discussed last time, the king in the first-known Robin Hood ballads is named as Edward; John and Richard are later additions whose inclusion technically transports Robin to a different historical dimension. If we want an outlaw tale that is authentically ‘early Plantagenet’, we should really get our heads around Fulk.

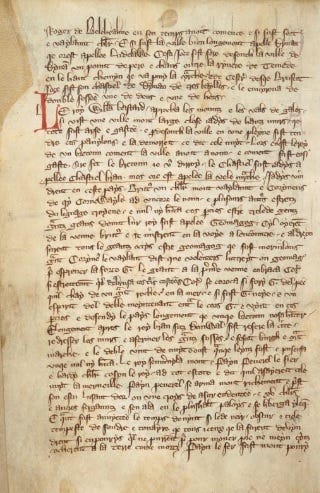

So what is Fulk all about? Let’s begin with the basics. There is one known medieval copy of Fouke le Fitz Waryn, which is bound in a large volume kept in the British Library. The volume contains all sorts: charters, religious offices for Edward II’s rebellious cousin Thomas earl of Lancaster, Latin maths puzzles, notes on astrology, palm-reading and fortune telling and much else besides. (You can browse the full manuscript in digital form here. Fulk’s tale is on folios 33r-60v.) This is a fourteenth-century manuscript, but it draws on older works, now lost.

Much like the volume it’s bound in, Fulk’s story is a mixed bag. It begins with a long section of family history, detailing the marriages and land deals of Fulk’s ancestors. It explains that the hero of the romance is the third Fulk of his line, and that his family has a claim over lands in the borders between England and Wales, dating back to the time of William the Conqueror. The preamble also sets up an important detail: letting the readers know that the Fitzwarins have been cheated out of their right to Whittington Castle and its lordships. Getting this back will be Fulk’s ultimate political goal, to be pursued in the second, longer, part of the tale.

Thereafter we are launched into a wild and eventful ride alongside Fulk, which blends real history, Robin Hood-type gangster escapades, dungeons-and-dragons fantasy and good, old-fashioned Homeric questing.

The real, historical elements differentiate this story from later English medieval outlaw tales (such as Robin Hood, Gamelyn and Adam Bell). They bear reasonably close relation to the following passage, which outlines the real Fulk’s career at the beginning of the real King John’s reign:

Fulk waged a guerrilla rebellion against the king between 1200 and 1203. His fifty-two adherents included his brothers William, Philip, and John, some Fitzwarine family tenants, and many younger sons of prominent Shropshire families. The king sent Hubert de Burgh with 100 knights to respond to this threat, but finally pardoned Fulk and his followers on 11 November 1203. Fulk paid 200 marks and finally received Whittington Castle in October 1204.

[‘Fitzwarine Family’ by Frederick Suppe in Oxford Dictionary of National Biography.]

The outlaw tale gives us an extended, somewhat garbled remix of these facts. Yet woven around them is something much bigger: a true epic of England, in which we find Fulk bouncing between all manner of scrapes, wearing numerous disguises and travelling as far afield as France, Scandinavia, Orkney and even Carthage. He is just as comfortable playing games of truth or dare with knights he encounters in the greenwood as he is fighting giants, or fantastical serpents and dragons in lands ruled by exotic heathens.

The outlaw tale is long and only loosely structured, but it is packed with high-octane action from start to finish. There are damsels. There is treasure. There are brawls. There are ships. There is a simple view of morality, hammered home by regular reminders that this is a revenge tale.

Fulk swore an oath that fear of death would not deter him from taking revenge on the King, who by force had wrongfully disinherited him.

What binds everything together is Fulk’s character: he is as wily as Odysseus but as honest as the day. He stands, like any good outlaw, for natural justice, virtue and common sense; it is these qualities, as much as his Jack Reacher-like physical prowess and proficiency at slaughter and violence, which see him through his many adventures. Fulk’s word is his bond, and all liars and traitors his enemies. We root for him, in an uncomplicated fashion, even though deep down we realise he is a ruthless murderer whom it would have been safer not to know.

Like Robin Hood, Fulk is religious, although piety only really comes into his life at its end, when he goes blind and is given seven years to contemplate the mysteries of the Almighty - a form of penance which implicitly excuses him any serious punishment in the afterlife for all the hundreds of heads he has lopped off. When he is finally buried at Whittington Castle (in the real world Fulk died in 1258), the story asks that God have mercy on his soul. Somehow, despite everything, we suspect He probably will.

Should more people read Fulk Fitzwarin today? Yes - even if just to compare it with the tales of Robin Hood. Those later stories plainly owe much to Fulk’s narrative, either directly or (more likely) in some more complex transmission relationship. In fact, Fulk is to my mind even more interesting than Robin Hood. His legend is a brilliant example of an older genre of English outlaw stories such as Eustache the Monk and Hereward the Wake, both of which we can discuss in future posts in this series.

It is more historical than Robin Hood, but at the same time more fantastical. Yet it also has striking similarities to the justice-obsessed fifteenth-century tales, with which we are much more familiar. It is an outlaw story that seems to look forward and backwards at the same time.

More than any of that, though, Fulk is tremendously good fun, and occasionally very funny. At one point midway through his tale, Fulk disguises himself as a monk to escape a gang of knights trying to bring him to justice. Trussed up in his habit and leaning on a knobbly stick, he banters with the men who are looking for him.

“Well, here is a fat and burly monk. He has a belly big enough to hold two gallons of cabbage,” [said one of the knights]. Without a word, Fulk raised his big staff and struck the knight such a blow beneath the ear that he fell senseless to the ground.”

History, fantasy, violent humour and morality, all in one place? It doesn’t get a lot more Hollywood than that. Perhaps one day soon Fulk Fitzwarin will have his own moment in the limelight. I rather think he deserves it.

*Note to attentive readers who thought I’d be reviewing Kit Harington in Henry V… I got the dates muddled up. I’m an idiot. Next week….

I’d love to be remembered as the guy who kicked King John in the chest

Brilliant story telling yourself there Mr Jones!

Ooh how many 'King John's' have we all wanted to kick in the chest over the years?

I always love looking at manuscripts as they are a time gone by, which is both Alien and similar.. It always amazes me as I gaze in wonder; there was someone with thoughts and feeling writing this epic or minutea in person.. I then have to read the tranalation to know what the hell it is about!